Issue No. 28

Welcome to Substack.

It may look different but my content is the same. You’ll notice a pay subscription option, don’t worry, there are no paywalls here, my content will always be free. The subscriptions are there in case you feel like supporting my work and the arts one step further. My archive of essays is now easier to browse, comment on and read. But enough with the platform, let’s get to the good stuff.

Three National Parks

The Yosemite

A long time ago there was a gentle valley high in the mountains whose sides were not steep, where ancient grassed meadows fed the giant mammoth and the trees grew tall beyond all imagination. The soft ground was a garden of plants and the leaves stretched ever upward in silent conquest. The rocky walls, veiled in summer mist, angled softly down no more than gentle slopes.

Then one day a wind blew from the North and all was changed. The gentle river valley was consumed by a sea of ice. Growing ever deeper it consumed all in its slow crawl West. The ice was very heavy and very cold and nothing lived where once it flourished.

And then the ice left, melted. The mammoth had all died and where once the gentle rock sloped was now sheer in scope. Rising from the once soft river valley, solid rock cliffs thousands of feet high loomed in granite cathedral grace touching the last rays of the setting sun.

A new valley was born. And the trees and the grasses and the flowers all came back. In early stillness the sounds of creaking wood and the soft flutter of morning birds echo off sheer walls. Falling waters cascade through mist, falling from above, channeling a way through a lush meadow of life, protected by granite and lost to the world without.

…

What I’ve found in these mountains changed my life. I’m not the first to have this happen after experiencing this place. The Yosemite does that. Photographers, writers, mountaineers, painters, climbers, poets, musicians, sculptors, wood blockers, charcoalists, aerialist have all been swooned by its embrace. I first came here at a young twenty, a bit of a climbing vagabond, with a used Nikon 35mm camera and not enough gas money to get home. Yosemite Valley is the pole star for climbing and that was partly why I first came. That and my father’s musings of Kerouac and wine and his own mountain obsession. With this I ran south, away from family, away from friends, away from myself. I had a road map and a direction and the long memory of a family mythos of the Yosemite. All of this reached north and pulled me south. I entered the valley that first time in the dark and found a dusted place to sleep in Camp IV, the climbers camp. I unrolled my sleeping bag on the dirt, crawled in and fell asleep to the chatter of camp.

Morning, and with it a chill of dry spring air, and up through the ponderosa’s long needles, past the cawing ravens, the granite stretched beyond all imagination. I laid and stared. And stared. And stared. I was in a cathedral, my cathedral. I knew then why people pray to gods unseen. I was laying beneath the abode of angels who reached down with stone fingers to bless my soul with something akin to spiritual enlightenment. I didn’t climb a thing that first time in the Yosemite. Instead I wandered in rapturous ecstasy, eager to drink it in, to bathe myself in its glorious light, in its dusted pine and mountain air. I found trails used and unused high over the valley, trudging through spring snow drifts and scrambling up granite slabs tucked away deep in the recesses of Tenaya Canyon and high along the backside of Half Dome. I fumbled at making images. I knew then what Muir knew, what Thoreau was getting at, what Kerouac found here, why Han Shan tucked himself away scratching his poems on rocks and trees.

Death Valley

A swirling cloud of dust trails behind me. The long dirt road is twisty and rutted. At the end of the road is a dry lake bed where the rocks move. How they move has been solved and it’s a wonderful scientific story, read about it here. But I’m not here for the explanation, I’m here for the visual mystery. These rocks only exist at the far southern end of the playa. I get there in the late evening and find a place to lay my blanket to sleep. I awake before dawn and wander over to the dry lake bed. Morning air in the Mojave is the most still I’ve ever experienced. Not a breath of wind stirs, no birds, no movement accept the long etched trails of these stones. There are lots of them and I walk around until I find a small, singular one I can frame in simplicity. The light is changing slowly, and with my tripod setup, camera framed and exposure set I capture a single frame and lay down on the hard dry lake.

This desert tingles in its inherent harshness. Death Valley is big. Really big. Without the five gallon water jug, gas tank half full, and bag of food sitting back at camp, I wouldn’t last out here very long. But I have those things so I can focus not on surviving but on the next order up, the creative and transcendent.

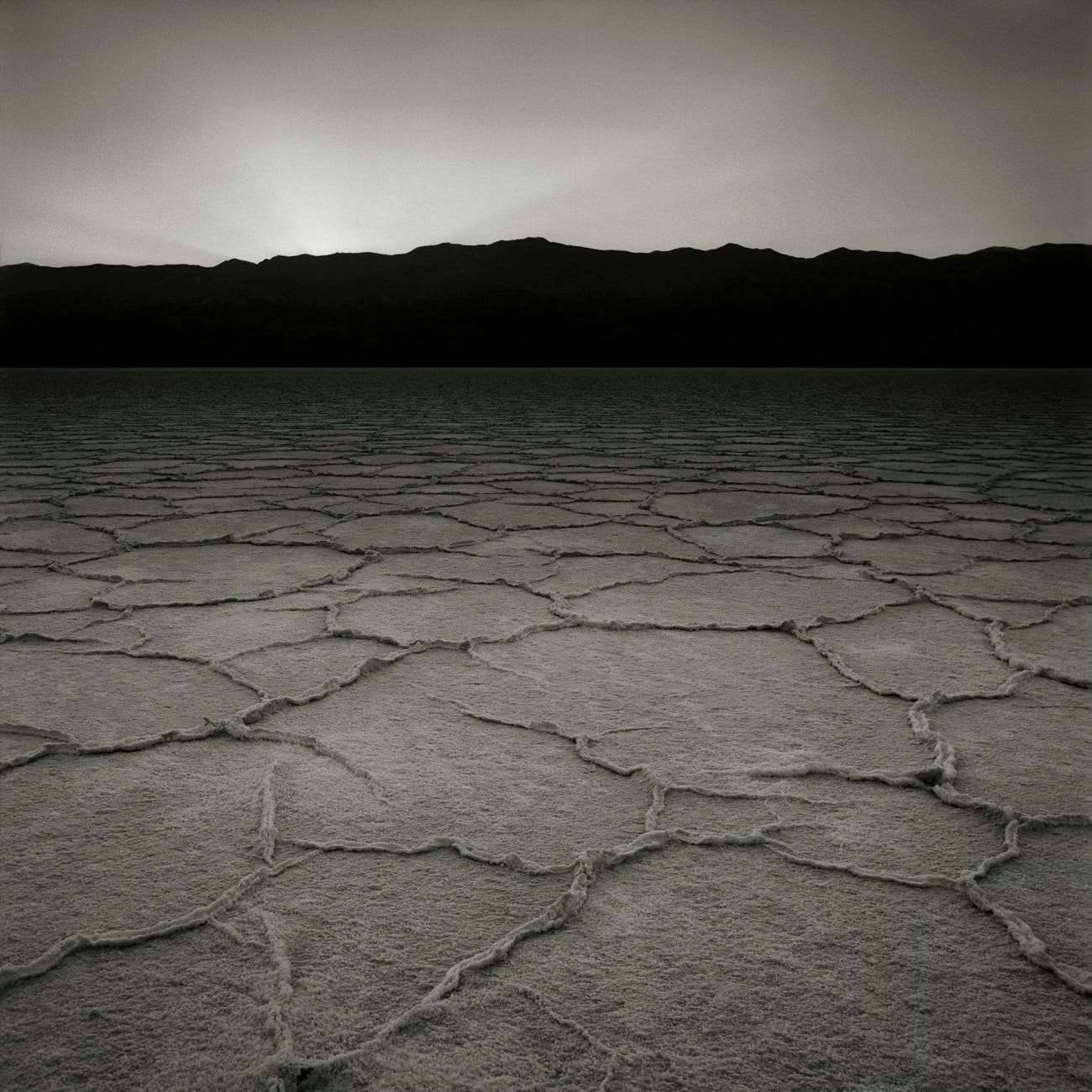

The Death Valley landscape yields to this harshness. Clean lines, strong tonalities, open air. Pure stillness. Time slows here. It’s the defining feature of the desert I love most. It’s now evening, just past sundown, Badwater, 282 feet below sea level. I walk a mile or more out onto the dried salt and minerals. The patterns left behind look like a web of geologic neurons stretching to the horizon. It’s all a kind of receding otherworld. I want this print to have a little foreground highlight so I make a note in my journal to do that later. As an artist I have a particular perspective in each print I want to convey. But when it leaves my hands for yours, it’s no longer my print and what you bring to it is individually all yours. I’ve done my work. The best art stimulates an unspoken conversation between artist and audience. What that conversation is is unique to the two involved, even if they never meet or speak a word together.

The Redwoods

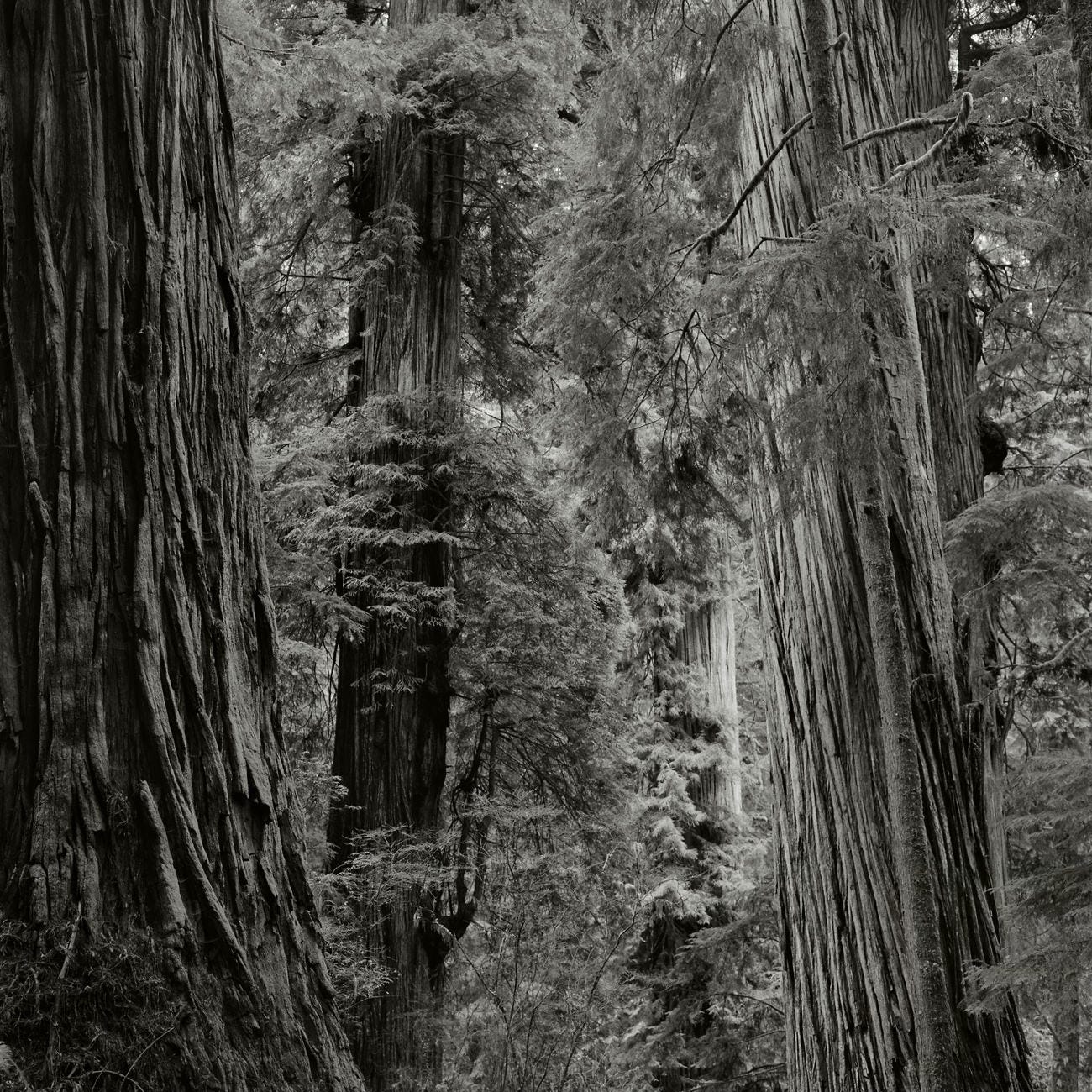

It is unlike any forest on Earth. It is of another time, another era, belonging to animals long since gone. To walk under the canopy of these forested giants is to confront the very smallness of our existence. It was walking here that my wife first felt the movement of our daughter. It was under these trees, years before, that I committed myself to the art of landscape photography. But it’s not an easy place to photograph because to fully appreciate the sheer scale of these plants, scale is exactly what is needed and I don’t put humans in my landscape work. So I shift my expression to an interesting idea. To shoot the forest in a way to limit what is known about it; no roots, no tops, no sky. Within these limitations having a balanced tonality that borders low contrast to keep the eye always moving. It’s an expression of a forest, not a forest unto itself.

Old growth Redwood is an experience of magnificent chaos. It is confused and balanced in its wonderful pith of life. They loom, not in dominance, but in the grace note of the forever. They should be called thus ‘the forever tree’. But it is not so. The redwood groves of today are but a trace of what once was a vast coastal range stretching the length of California to Northern Oregon. A few isolated groves are all that's left of a tree that can only die by wind or by the saw. It is up to our species to steward these last remaining giants. To walk under these canopies is to feel full of vigor. That these forest have been universally slaughtered is a moral crime. The remaining small tracts need continual protection for if they go that will be it for a thousand years. I’m an artist conservationist not an activist. It’s the best way I know how to show something special in nature and these forest spaces are special. They don’t need us but we need them.

New Work

Updates

I regularly update my website with fresh work and new galleries. Take a wander around, you’ll see an entirely new menu item that now showcases my commercial work. This work has been a fun curation and now showcase. I’d love to hear what you think of it!